THE PERFECT STORM: How Government, Universities, Banks, and Culture Created America’s Student Debt Crisis

Abstract

The American student debt crisis is often framed as a debate between personal responsibility and systemic failure, but the reality is far more complex. This paper examines the cumulative forces — political, economic, institutional, and cultural — that transformed higher education from a public good into a personal financial burden. Through historical analysis, policy examination, financial industry influence, and cultural critique, it shows how a perfect storm of decisions and dynamics created today’s crisis. It also highlights the human cost across racial, class, and generational lines, the mental health consequences, and the emerging threat to national competitiveness. Solving this crisis requires an honest reckoning with the full architecture that created it — not just superficial political debates.

Thesis Statement

The American student debt crisis is not a singular failure of personal responsibility or a simple consequence of rising college costs; it is the cumulative result of decades of deliberate political decisions, systemic financial exploitation, state disinvestment, cultural mythmaking, and unchecked institutional greed — creating a perfect storm that now traps borrowers across racial, class, and generational lines, imposes devastating psychological and economic costs, and threatens America's long-term social and global competitiveness. Only by confronting the full architecture of this crisis can meaningful reform be achieved.

Introduction

Across the United States, millions of borrowers are bracing for the financial shock of student loan repayments resuming, caught between political outrage and personal survival. On social media, the right mocks borrowers as entitled and irresponsible, while the left frames loan repayment as a new form of systemic oppression. Yet behind the noise, the lived reality for many borrowers is more complex, more painful, and more honest: a generation who took on debt in good faith, who bear personal responsibility for their loans, but who are also drowning under the weight of a system that has been rigged against them for decades.

The roots of America’s student debt crisis stretch far beyond individual financial choices or isolated economic trends. What once was a higher education system built as a public good — affordable, accessible, and publicly funded — has been steadily dismantled since the 1970s. State disinvestment shifted the cost burden onto families. Federal policy transformed financial aid from grants to predatory loans. Universities evolved into prestige-chasing corporations. Meanwhile, banks, loan servicers, and financial institutions captured the profits, lobbying lawmakers to make student debt nearly impossible to escape. Beneath it all, a powerful cultural myth — that college was always "worth it" at any cost — fueled endless borrowing without regard for economic realities. This perfect storm, compounded by racial and class disparities, rising mental health crises, and even an emerging brain drain of American talent abroad, has created a disaster far greater than a simple failure of budgeting or personal foresight.

I. The Early Years: When College Was a Public Good

Before the explosion of student debt, American higher education was neither a private luxury nor an individual financial gamble. It was seen — at the highest levels of government, industry, and culture — as a strategic public investment in national strength, technological leadership, economic security, and democratic stability. From the 1940s through the early 1970s, higher education in the United States was designed, funded, and promoted as an essential pillar of the American social contract.

This philosophy was crystallized through the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 — the GI Bill — signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The GI Bill provided full tuition, fees, books, and generous living stipends to millions of returning World War II veterans. By 1956, over 7.8 million veterans had accessed educational benefits, flooding colleges and universities and triggering one of the largest expansions of human capital in world history. The policy was not simply charity: policymakers understood that rebuilding the American economy, preventing postwar unemployment, and sustaining U.S. geopolitical dominance would require a vastly more educated workforce.

However, the benefits were not evenly distributed. Due to systemic racism, Black veterans in the South and elsewhere often faced discrimination from universities that denied them admission or provided substandard opportunities. Nonetheless, even with these inequities, the GI Bill catalyzed an unprecedented mass access to higher education for millions of Americans, permanently altering the relationship between ordinary citizens and college opportunity.

Simultaneously, Cold War pressures reinforced the idea that broad educational attainment was a matter of national survival. Following the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik in 1957, panic spread across the United States that the nation was falling behind technologically. In response, the federal government poured unprecedented funding into science education, engineering programs, and research institutions. The National Defense Education Act of 1958 invested heavily in math, science, and language training, particularly in universities. College access was reframed not merely as an economic opportunity but as Cold War arsenal — vital to maintaining American supremacy against the communist bloc.

This national investment was not abstract. States rapidly expanded public university systems:

The California Master Plan for Higher Education (1960) made the University of California, California State, and community colleges widely accessible — nearly tuition-free.

The State University of New York (SUNY) and City University of New York (CUNY) massively grew under similar philosophies: public universities would serve the public good directly, not private profit.

By the late 1960s, higher education was treated similarly to highways (the Interstate System) and military bases — as national infrastructure, essential to economic development, scientific leadership, and democratic health.

The Higher Education Act of 1965, signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson as part of his broader "Great Society" reforms, cemented this ethos at the federal level. Johnson framed access to college as a civil right, stating:

“Education is no longer a luxury. Education in this day and age is a necessity.”

The Act created a structured federal financial aid system, including grants — particularly Pell Grants — for low-income students. Importantly, the original design of federal financial aid was grant-based, not loan-based. It reflected a belief that lifting Americans into higher education was an investment in collective prosperity, not a debt burden to be individually borne.

Economically, the returns on this public investment were immediate and profound:

From 1940 to 1970, the proportion of Americans with at least some college education more than tripled.

College graduates entered a rapidly growing middle class, purchasing homes, cars, and raising standards of living.

Real GDP growth during the postwar boom averaged over 4% annually, driven in part by a better-educated workforce.

The United States led the world in technological innovation, from aerospace to computing to pharmaceuticals, reinforcing global dominance.

Financially, college was remarkably affordable:

In 1970, the average tuition at a four-year public college was approximately $394 per year — about $3,000 in today’s dollars.

Meanwhile, states covered approximately 75% to 80% of public college operating budgets.

Student loans were rare, reserved for modest, supplementary expenses rather than basic attendance costs.

Most critically, there was a social consensus that education was not a commodity, but a public right and a collective investment in the future. Students entering public colleges did not see themselves as customers; they were participants in a national project of opportunity, innovation, and security.

Yet, this golden age of publicly accessible higher education would not last. Political, economic, and ideological shifts in the 1970s would begin dismantling the very foundations that made it possible, setting the stage for the debt-driven crisis that defines American higher education today.

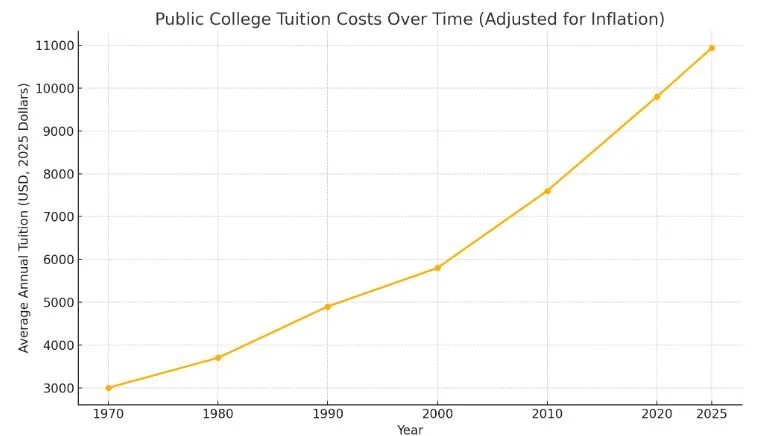

Figure 1: Public College Tuition Costs: 1970 vs 2025 (Adjusted for Inflation)

Figure 1 illustrates the dramatic increase in average public university tuition over time, adjusted for inflation. In 1970, a year of tuition at a four-year public university averaged approximately $394 ($3,000 in 2025 dollars). By 2025, average annual tuition has risen to over $10,900. This shift reflects the transition from an era of public investment to an era of individual financial burden through widespread student lending.

(Data Source: U.S. Department of Education, College Board Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2024

II. The Shift: State Disinvestment and the Birth of the Student Loan Explosion

While the postwar decades treated higher education as a vital public good, this consensus began to fracture dramatically during the 1970s. A convergence of political, economic, and ideological forces — recession-driven budget crises, taxpayer revolts, the rise of neoliberal market philosophies, and shifting federal priorities — fundamentally transformed the way higher education was funded. Over the course of just two generations, America moved from a model where public investment enabled mass college access, to one where students themselves were expected to bear the rising costs through personal debt.

The initial economic shocks came with the stagflation crisis of the 1970s. As inflation soared and economic growth stalled, state governments faced mounting budgetary shortfalls. Under intense pressure from voters to cut taxes and curb spending, states began reducing allocations to public universities. One of the most symbolic events was California’s Proposition 13 in 1978 — a landmark taxpayer revolt that capped property taxes and severely constrained state revenue. Following its passage, California, once the model of free or nearly-free public higher education, began systematically slashing university funding. Other states soon followed.

Federal policy shifts compounded the problem. In 1978, Congress passed the Middle Income Student Assistance Act (MISAA), a law that unintentionally accelerated the replacement of grants with loans. Originally intended to help middle-class students, the Act vastly expanded eligibility for federal student loans, extending borrowing opportunities to families who previously would have received direct public aid. The federal government began to redefine its role: not as a guarantor of low-cost education, but as a lender.

The broader philosophical shift was rooted in the emerging neoliberal consensus of the late 20th century. Economic thinkers, business leaders, and political figures across party lines began to argue that higher education was primarily a private good rather than a public investment. According to this logic, since college graduates individually benefited through higher lifetime earnings, it was appropriate — even necessary — that they personally finance their education, rather than society subsidizing it.

This ideological shift intensified during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. As governor of California in the 1960s, Reagan had already clashed with public university leaders over student protests, slashing higher education budgets and introducing the first tuition fees at the University of California system. As President (1981–1989), Reagan proposed slashing federal financial aid budgets by up to 50%, arguing that education was a personal responsibility. While Congress resisted the most extreme cuts, the direction was clear: federal grants stagnated or declined in real value, while loan programs expanded.

Data confirms the transformation.

In 1975, state appropriations made up roughly 75% of public university revenues.

By 2025, that figure had fallen to below 30% nationally.

Simultaneously, federal Pell Grants — once covering nearly 80% of public college costs for low-income students — now cover less than 30% of the typical public university bill.

Meanwhile, federal student loan disbursements exploded, growing from $12 billion in 1980 to over $90 billion annually by 2025.

State Funding for Higher Education as a Percentage of University Budgets (1970–2025)

Figure 2: Shows the steady decline in the percentage of public university budgets covered by state funding, falling from approximately 75% in 1975 to under 30% by 2025. As states disinvested, tuition soared, and student loans became the primary mechanism for financing higher education.

(Data Source: State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2024)

The consequences of these shifts were immediate and devastating. Public universities, facing shrinking state support, began raising tuition dramatically to make up the difference. Students who once could have graduated with minimal or no debt now found themselves forced into taking on large, long-term federal loans simply to attend institutions that had been nearly free to previous generations.

Importantly, this disinvestment and debt explosion were not confined to elite institutions or private colleges. They affected ordinary Americans — middle-class, working-class, and first-generation college students — at public universities across the nation.

The groundwork had been laid: the collapse of the public funding model, the expansion of federal loans, the ideological reframing of education as a private commodity.

Student debt, once a rare exception, was on its way to becoming the norm.

III. The University Arms Race: Prestige Over Affordability

As state support for higher education declined and the financial burden shifted increasingly onto students, American universities entered a new era — one defined less by their commitment to public service and more by fierce competition for prestige, rankings, and revenue. No longer buffered by stable public funding, colleges and universities found themselves locked in a relentless arms race to attract students, donors, and visibility. In the process, the very economics of higher education were transformed, driving tuition costs even higher and worsening the reliance on student loans.

At the heart of this transformation was the growing influence of national college rankings systems, most notably the U.S. News & World Report rankings, first published in the 1980s. University leaders quickly realized that climbing in these rankings — which often weighted factors like faculty resources, student amenities, alumni donations, and admissions selectivity — could lead to increased applications, higher tuition, larger endowments, and greater political clout. In an environment where funding was scarce and competition was fierce, prestige became currency.

This led to a rapid escalation in university spending on what economists have termed "non-academic enhancements."

Luxury dormitories outfitted with private bathrooms, flat-screen TVs, and designer furnishings replaced traditional residence halls.

Gourmet dining options offering sushi bars, vegan cafes, and artisanal coffee shops replaced simple cafeterias.

Fitness centers rivaling private health clubs, lazy rivers, climbing walls, and sports stadiums costing hundreds of millions of dollars became standard.

Meanwhile, another profound shift occurred inside the administrative structures of universities. Rather than expanding primarily their instructional faculty to educate growing student bodies, colleges massively expanded their administrative bureaucracies.

Between 1975 and 2025, the number of non-teaching administrative and professional staff at American colleges and universities increased by over 300%, far outpacing the growth in enrollment or faculty hiring.

This phenomenon is captured by Bowen’s Rule, articulated by economist Howard Bowen:

“The dominant goals of institutions are educational excellence, prestige, and influence. There is virtually no limit to the amount of money an institution could spend for seemingly fruitful educational ends. Institutions raise all the money they can — and spend all the money they raise.”

In essence, universities behaved like corporations operating without traditional market constraints: since there was an endless societal demand for college degrees, institutions could raise costs continually without fear of losing customers.

Data illustrates this administrative explosion clearly.

In 1975, administrative staff made up roughly 20% of total university employees.

By 2025, administrative staff comprised more than 50% of total personnel at many public and private universities.

Instructional expenditures (actual teaching costs) remained relatively flat, while non-instructional spending (marketing, student services, facilities, athletics) soared.

Figure 3 illustrates the disproportionate growth of administrative staff compared to instructional faculty over the past fifty years.

Figure 3: This figure shows the explosive growth of administrative staffing relative to instructional faculty hiring at U.S. colleges and universities. Administrative roles increased by over 300% between 1975 and 2025, significantly outpacing faculty growth and contributing to tuition inflation.

(Data Source: Delta Cost Project; American Council on Education.)

The result of these dynamics was predictable: soaring tuition rates and escalating student debt.

Rather than adapting to reduced state support by streamlining operations or maintaining affordability, universities engaged in a costly competition for status, subsidized by an increasingly debt-burdened student population. Students were enticed not only by academic offerings, but by promises of lifestyle — living in luxury, exercising in elite gyms, and enjoying amenities previously unimaginable in higher education.

Thus, the logic of the arms race directly collided with the logic of public access.

College became not only more expensive, but fundamentally rebranded: not as a public service or patriotic investment, but as a high-priced consumer experience — one that students were expected to finance personally, often at catastrophic long-term cost.

This shift laid the groundwork for the next critical evolution: the financialization of student debt itself, as lenders, servicers, and financial institutions recognized the profit potential embedded in America’s reengineered higher education system.

IV. The Role of Financial Industry Capture

As tuition soared and students were pushed into borrowing unprecedented amounts to access higher education, a new and powerful force entered the arena: the financial industry. Recognizing the vast profit potential in an economy increasingly dependent on student debt, private lenders, loan servicers, and associated lobbyists systematically reshaped the legal and regulatory landscape to protect and expand their interests.

Student lending became big business — and students became the collateral.

The most symbolic and consequential moment came with the privatization of Sallie Mae.

Originally created in 1972 as a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) to make education loans accessible, Sallie Mae was partially privatized in 1997 and fully privatized by 2004. Once liberated from its public mission, Sallie Mae rapidly transformed into a profit-maximizing corporation, heavily investing in lobbying, marketing private loans, and opposing regulations that might protect borrowers.

Following Sallie Mae's lead, a vast industry of private lenders and loan servicers (companies that manage billing and payments on federal loans) emerged, including Navient, Nelnet, MOHELA, and others. These entities recognized that servicing debt — and keeping borrowers trapped in cycles of deferment, forbearance, and interest accrual — was far more profitable than helping borrowers repay.

To protect and expand these revenue streams, the industry poured millions into political lobbying.

Between 2000 and 2025, student loan servicing companies spent over $300 million lobbying Congress and federal regulators.

Sallie Mae alone spent over $40 million during this period, targeting both Republican and Democratic lawmakers.

Major goals included blocking regulations that would ease repayment burdens and preventing restoration of bankruptcy protections for student loans.

One of the industry's most significant victories came with the passage of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, signed into law by President George W. Bush. The law made it nearly impossible to discharge federal and private student loans through bankruptcy — even in cases of extreme financial hardship.

Student loans became one of the few debts in American law (alongside child support and criminal fines) that were permanently "sticky", surviving unemployment, divorce, illness, and even bankruptcy itself.

The logic behind this policy was brutally simple: lenders could now offer loans without worrying about risk.

Borrowers could not escape repayment, no matter what happened in their lives.

Risk had been entirely shifted away from lenders and onto students and families.

Data underscores the scale of this transformation.

In 1990, student loan debt totaled approximately $120 billion nationally.

By 2025, total outstanding student loan debt surpassed $1.8 trillion — a more than 15-fold increase in just three decades.

Servicing companies extracted billions in fees, penalties, and interest profits, often while providing poor customer service and mismanaging repayment programs.

Figure 4 visualizes the rise in lobbying expenditures by student loan companies, paralleling the explosion of total student debt.

Figure 4: This figure illustrates the sharp rise in lobbying expenditures by student loan servicing companies between 2000 and 2025, paralleling the explosive growth of total outstanding student debt. Industry lobbying successfully influenced key legislation and regulatory frameworks to protect profits at the expense of borrowers.

(Data Source: OpenSecrets.org 2025.)

The capture of student lending by financial industry interests fundamentally altered the character of American higher education finance.

Where previous generations had attended college through public investment, students after 2005 increasingly did so through privately profited debt traps — engineered to be lifelong, difficult to escape, and economically punishing.

The student loan system was no longer merely a tool for access to education.

It had become a financial extraction machine, operating legally, politically protected, and devastatingly effective.

This evolution set the stage for the next critical dynamic: the cultural and psychological transformation that convinced millions of Americans to accept crushing student debt as a normal — even inevitable — rite of passage into adulthood.

V. Cultural Myths: "College is Always Worth It"

While political decisions and financial interests laid the groundwork for America’s student debt crisis, a deeper — and arguably more insidious — force sustained its expansion: a powerful cultural mythology that college was not simply valuable, but always worth it, at any cost, under any circumstances.

This narrative, promoted across media, schools, and even government programs, assured generations of Americans that higher education guaranteed success — financially, socially, and personally — regardless of the price tag or the field of study.

The roots of this myth can be traced to postwar realities.

In the 1950s and 1960s, attending college was a near-guaranteed path to upward mobility. The economy was expanding rapidly, wages for college graduates were rising, and higher education was still largely affordable. As such, the message that "college pays off" was empirically true — for a time.

However, as tuition rose, wages stagnated, and debt exploded, the realities underpinning this claim eroded — but the cultural messaging did not adjust. Instead, hyperbolic discounting (a behavioral economics phenomenon where individuals heavily favor immediate rewards over future risks) led students and families to underestimate the long-term burden of borrowing.

Similarly, optimism bias (the tendency to believe that one’s personal outcomes will be better than average) caused many to assume they would secure high-paying jobs immediately upon graduation, regardless of market trends or degree fields.

This psychological backdrop was reinforced by systematic misinformation:

High schools, under pressure to boost college-going rates, encouraged almost all students to pursue four-year degrees, often without serious discussion of costs, financial aid, or alternatives like vocational training.

Parents, having seen the postwar boom, believed college was the only legitimate path to middle-class security, often pushing children toward traditional four-year universities without full understanding of modern debt risks.

Media and popular culture glamorized college life while largely ignoring the realities of repayment, default, or underemployment.

Government programs, like FAFSA, were structured around the assumption that nearly all students should borrow if necessary to attend college — framing debt as an investment, not a risk.

Compounding the problem was the average lifetime earnings data frequently cited to justify borrowing.

Policymakers, journalists, and financial advisors regularly quoted studies showing that college graduates earn, on average, $1 million more over their lifetimes than high school graduates. However, this figure obscured critical nuances:

It averaged earnings across all degrees — from engineering to fine arts — despite massive disparities between fields.

It did not adjust for debt loads, cost of attendance, or opportunity costs of lost income while studying.

It assumed stable economic conditions similar to the postwar boom — conditions that had largely evaporated by the 2000s.

The reality was far more complex:

A computer science graduate from MIT could expect strong ROI on education debt.

A graduate with a sociology degree from a non-selective regional university often could not.

Median earnings for many degree fields (e.g., humanities, arts, education) were insufficient to justify high debt loads.

Data highlights the mismatch.

According to the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce (2024), the median starting salary for humanities majors in 2024 was around $42,000/year, compared to a starting debt load averaging $30,000–$40,000.

For engineering graduates, median starting salaries were $75,000–$80,000/year — allowing faster repayment.

Figure 5 visually represents the divergence between degree fields, debt loads, and likely earnings.

Figure 5: This figure illustrates the mismatch between typical student debt levels and median lifetime earnings across different academic majors, highlighting the risk of debt non-viability for low-earning fields.

(Data Source: Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, 2024.)

The cultural mythology that "college always pays" thus functioned as ideological infrastructure — providing cover for escalating costs, expanding loans, and declining public investment. Students were taught not to question the price of education, much less demand structural reform.

If they struggled, it was framed not as a systemic failure, but as a personal failure — poor choices, insufficient work ethic, or bad luck.

This narrative served powerful interests well.

Universities could raise prices without serious resistance.

Loan companies could expand debt portfolios with minimal scrutiny.

Politicians could avoid confronting the collapse of the public funding model.

Ultimately, the myth of college’s guaranteed value helped engineer a system where millions of Americans willingly — even eagerly — borrowed tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars under false pretenses, entering a labor market that increasingly could not justify the cost.

The human cost of this myth would soon become tragically apparent — not just in financial terms, but in the mental health, social mobility, and generational aspirations of an entire generation.

VI. The Human Cost: Inequality, Mental Health, and Generational Damage

While the structural transformation of American higher education was rooted in political, economic, and cultural shifts, the ultimate consequences have been lived — often painfully — by individual borrowers and families. The student debt crisis is not a distant policy failure; it is a profound personal and social disaster that has exacerbated racial and class inequalities, triggered widespread mental health crises, delayed life milestones crucial to economic stability, and increasingly threatens America’s global competitiveness.

Debt burdens are not distributed equally across the population. Rather, they reinforce and deepen existing inequalities. Black borrowers, for example, face significantly higher levels of student debt than white borrowers, even when controlling for degree attainment. Studies show that Black college graduates owe, on average, $25,000 more than their white peers four years after graduation. Furthermore, default rates among Black borrowers are approximately five times higher than those among white borrowers, reflecting broader structural inequities in employment, income, and access to generational wealth. Similarly, first-generation college students and students from low-income families are more likely to borrow larger amounts and experience repayment difficulties. The promise of higher education as an equalizing force has, for many, become a mechanism of further stratification.

The psychological consequences of student debt are equally alarming. Research from the Journal of American College Health (2024) indicates that graduates with significant debt burdens are twice as likely to report clinical levels of depression compared to their debt-free counterparts. Anxiety, chronic stress, and sleep disturbances are also notably higher among indebted individuals. The perception of debt as inescapable — particularly given the legal restrictions on discharging student loans through bankruptcy — creates a pervasive sense of hopelessness. This despair is not merely anecdotal; longitudinal studies have found correlations between high student debt levels and increased suicide risk among young adults. The crisis extends beyond economic metrics, eroding the mental health of an entire generation.

The burden of student debt also extends beyond the young. Increasingly, parents and even grandparents have been drawn into the system through Parent PLUS loans and other co-signing arrangements. Over 3.7 million Americans over the age of 60 currently owe outstanding student loan balances. Many face wage garnishment, tax refund seizures, and even reductions in Social Security benefits to service these debts. Far from enabling generational uplift, the current system often traps entire families in cycles of intergenerational financial instability, undermining the very purpose for which education loans were originally intended.

Student debt has profoundly reshaped the trajectory of adulthood for millions of Americans. Homeownership, historically a primary driver of middle-class wealth, has been delayed or abandoned by large swaths of millennial and Generation Z borrowers. Marriage rates have declined, with many citing financial insecurity related to student debt as a major reason for postponement. Family formation has similarly been delayed, with indebted individuals reporting an unwillingness or inability to bear the additional costs associated with raising children. These delays have cumulative economic effects, reducing long-term wealth accumulation and exacerbating demographic shifts such as declining birth rates.

Perhaps most concerning for America’s long-term future is the emerging phenomenon of "brain drain." Historically, the United States attracted the best and brightest minds from around the world, while its own citizens enjoyed unparalleled educational and economic opportunities domestically. Today, however, an increasing number of American graduates are seeking opportunities abroad — particularly in countries like Germany, Canada, and the Netherlands — where healthcare is affordable, education debt is minimal, and the cost of living is manageable. Graduate programs in Europe are now heavily marketed to American students facing insurmountable debt at home. The United States risks not only the financial impoverishment of its current generations, but also the permanent loss of its intellectual capital.

Figure 6: This figure summarizes the major human impacts associated with student debt in the United States, including heightened anxiety and depression, delayed homeownership and family formation, elder poverty driven by Parent PLUS loans, and the emerging phenomenon of graduate emigration abroad ("brain drain"). The psychological and economic burdens of student debt have profound consequences across multiple generations.

(Data Sources: Journal of American College Health, Pew Research Center, U.S. Department of Education, 2024–2025.)

These human consequences are not incidental. They are the predictable outcomes of a system that restructured education from a public good into a private risk. They represent a profound and ongoing national crisis, not just of finance, but of morality, public policy, and social sustainability.

VII. Today’s Political Freakout: Missing the Bigger Picture

The resumption of federal student loan payments in 2025 reignited a predictable storm of political rhetoric across the American landscape. On social media, in congressional speeches, and in news outlets, polarized narratives emerged with renewed ferocity. Yet despite the noise, the underlying discourse — on both the right and the left — largely obscures the true complexity of the student debt crisis. Political actors have seized upon borrower suffering not to propose meaningful solutions, but to reinforce ideological identities, misrepresent root causes, and deepen partisan divides.

Among many figures on the political right, the crisis is frequently framed in terms of personal irresponsibility. Borrowers are portrayed as having willingly entered into contracts and are therefore morally obligated to repay their debts, regardless of circumstance. Pundits and politicians emphasize traditional virtues of self-reliance, thrift, and accountability, often dismissing borrower distress as evidence of moral or financial weakness. Calls for forgiveness or reform are attacked as "socialism" or "entitlement culture," reinforcing a broader narrative that frames government intervention as illegitimate.

While there is a kernel of truth to the emphasis on personal responsibility — borrowers do sign contracts and benefit from education — the framing ignores the broader systemic architecture that engineered widespread indebtedness. It disregards the shift from public investment to private risk, the collapse of grant-based aid, the predatory behavior of financial institutions, and the broader economic forces that render repayment untenable for many. In doing so, right-wing rhetoric reduces a structural failure into an individualized moral failing, precluding serious discussion of systemic solutions.

Conversely, on the political left, the student debt crisis is often framed primarily through the lens of structural oppression. Debt is characterized as a tool of economic injustice, disproportionately harming marginalized communities and reinforcing racial, class, and gender inequalities. Activists demand widespread or total forgiveness, framing debt relief as a moral imperative to achieve social justice. Progressive politicians frequently position debt cancellation as an act of reparative equity, necessary to rectify broader patterns of systemic discrimination.

Yet here, too, crucial complexities are frequently elided. The left's framing often implies that all student debt is equally illegitimate, regardless of degree choice, institutional quality, borrowing levels, or repayment capacity. It underemphasizes the contractual nature of loans, the heterogeneity of borrower outcomes, and the economic realities of funding large-scale cancellation programs. Furthermore, progressive proposals sometimes neglect the deeper issue of cost inflation in higher education, meaning that even full debt cancellation would leave future generations vulnerable to exactly the same crisis unless structural reforms accompany relief.

Both sides, therefore, engage in forms of bad faith: the right denies systemic collapse, the left denies individual agency and economic constraints. Both use the suffering of borrowers primarily as a rhetorical weapon, rather than confronting the full reality of how the student debt crisis was created, sustained, and exacerbated over decades by bipartisan policy decisions, market failures, cultural myths, and financial capture.

Polling data reinforces the public’s exhaustion with this dynamic. Surveys conducted by Pew Research Center (2025) show that a majority of Americans, including a substantial share of borrowers themselves, express skepticism toward both blanket forgiveness proposals and punitive repayment mandates. Rather than embracing polarized solutions, nearly half of Americans favor targeted reforms aimed at protecting the most vulnerable borrowers while restoring the affordability of higher education.

Figure 7: This figure illustrates American public opinion on student debt solutions in 2025. While political rhetoric often frames the debate in extreme terms, polling shows that a majority of Americans favor nuanced, targeted reforms rather than blanket forgiveness or punitive repayment. Nearly half of Americans (48%) support targeted relief and reforms over the more polarized options of full forgiveness (28%) or no forgiveness (24%).

(Data Source: Pew Research Center, 2025.)

This polling underscores the gap between political elites and the broader public. Most Americans recognize that addressing the student debt crisis requires both compassion and structural pragmatism — acknowledging borrower hardship without ignoring the need for systemic financial and institutional reforms.

The political debate around student debt thus mirrors broader patterns in American politics: complex problems are reduced to simplistic slogans, systemic failures are hidden behind cultural warfare, and policy discussions are subsumed by performative outrage. As long as the national conversation remains trapped in this polarized framework, meaningful reform will remain elusive. Real solutions require not merely assigning blame or issuing blanket absolution, but confronting the full architecture of a system that transformed higher education from a publicly supported good into a privately financed, debt-driven commodity.

Until that reckoning occurs, millions of borrowers — and the nation itself — will continue to pay the price.

VIII. Conclusion: Building Toward Real Solutions

The American student debt crisis did not arise from a singular moment of miscalculation, nor from the isolated irresponsibility of borrowers or lenders. It is the inevitable result of a decades-long convergence of political disinvestment, financial capture, cultural mythology, and systemic neglect. What was once a publicly supported path to opportunity has been transformed into a debt-financed gamble, in which the risks are socialized onto students and families while profits are privatized by institutions and financial intermediaries.

The historical arc is unmistakable. In the mid-20th century, higher education was treated as national infrastructure — funded through public investment, justified by Cold War imperatives, and celebrated as a pillar of democracy and prosperity. This model began to unravel in the 1970s, as tax revolts, budgetary crises, and ideological shifts framed education increasingly as a private benefit rather than a public good. State disinvestment, federal policy changes favoring loans over grants, the rise of prestige-driven spending within universities, and the financialization of student debt mechanisms accelerated the collapse of affordability.

Meanwhile, cultural narratives about the inherent worth of a college degree, regardless of cost or context, masked the growing dangers. Behavioral economics, social pressures, and misinformation combined to drive millions of Americans into borrowing patterns unsuited to the economic returns of their chosen fields. As a result, the crisis now touches every aspect of American life — from racial and economic inequality to mental health, from delayed family formation to diminished national competitiveness.

Political responses to this crisis have been predictably inadequate. Simplistic slogans, partisan blame games, and performative outrage have dominated the discourse, while serious structural reforms have remained elusive. Both blanket debt cancellation and punitive repayment demands fail to grapple with the deeper architecture of collapse.

Real solutions must move beyond ideological posturing. They must confront the system as a whole.

This requires:

Substantially increasing public investment in higher education at state and federal levels to restore affordability and reduce dependency on loans.

Implementing strict regulatory controls over tuition pricing and university spending, tying eligibility for federal aid to financial stewardship and cost containment.

Reforming federal loan programs to limit principal balances, reduce interest rates, and ensure genuine income-based repayment protections.

Restoring bankruptcy protections for borrowers facing genuine hardship, rebalancing the legal inequities that uniquely disadvantage student borrowers.

Reengineering cultural messaging to promote informed decision-making about education choices, including expanded support for vocational and technical education pathways.

Ultimately, America must reframe the debate.

The question is not simply whether borrowers should be forgiven, nor whether students are to blame. The true question is whether the nation will continue to view education as a consumable luxury financed by personal debt — or whether it will reclaim its earlier vision of higher education as a cornerstone of public prosperity, democratic vitality, and shared national strength.

Failure to act will not simply burden individual borrowers. It will erode the nation's human capital, widen social fractures, and cripple the American promise for future generations.

Rebuilding a sustainable, just, and accessible higher education system is not only possible. It is imperative.

The cost of inaction — in human, economic, and moral terms — will far exceed the investment required to restore what was once a defining strength of the American experiment.

References

American Council on Education. (2024). Trends in Higher Education Administrative Staffing 1975–2025. Washington, DC.

College Board. (2024). Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2024. College Board Publications. https://research.collegeboard.org

Delta Cost Project. (2024). Trends in College Spending: 1975–2025. American Institutes for Research.

Education Data Initiative. (2025). Average Cost of College and Tuition Rates Over Time. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/average-cost-of-college

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. (2024). The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings. Georgetown University. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/the-college-payoff-2024/

Journal of American College Health. (2024). Mental Health Outcomes Among Indebted College Graduates: A Longitudinal Study. American College Health Association.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), U.S. Department of Education. (2024). Historical College Tuition Rates and Trends. https://nces.ed.gov

OpenSecrets.org (Center for Responsive Politics). (2025). Lobbying Expenditures Database: Student Loan Servicing Companies 2000–2025. OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org

Pew Research Center. (2025). Public Opinion on Student Debt Forgiveness and Higher Education Reform. Pew Research Center. https://pewresearch.org

State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO). (2024). State Higher Education Finance: FY2024 Report. https://sheeo.org

Placement of Figures and Corresponding Sources:

Figure 1: Public College Tuition Costs (1970–2025)

Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (2024); College Board (2024)Figure 2: State Funding for Higher Education as a Percentage of University Budgets (1975–2025)

Source: State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (2024)Figure 3: Growth of Administrative Staff vs Faculty Hiring Rates (1975–2025)

Sources: Delta Cost Project (2024); American Council on Education (2024)Figure 4: Student Loan Servicing Company Lobbying Expenditures (2000–2025)

Source: OpenSecrets.org (2025)Figure 5: Median Lifetime Earnings by Major vs Average Student Debt Load

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (2024)Figure 6: Summary of Human Impacts of Student Debt

Sources: Journal of American College Health (2024); Pew Research Center (2025); National Center for Education Statistics (2024)Figure 7: Public Opinion on Student Debt Solutions (2025)

Source: Pew Research Center (2025)

Disclaimer:

This paper is intended for academic and informational purposes only. The analyses, opinions, and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official views of any institution, organization, or agency. While every effort has been made to accurately represent historical data, legislative developments, and contemporary issues regarding student debt and higher education finance, readers should consult primary sources and official reports for verification. This work does not constitute legal, financial, or policy advice. All figures, data points, and cited sources are used in good faith and were accurate to the best of the author's knowledge at the time of writing.